Leonid Averbuch

Odessa

Ukraine

Interviewer: Nicole Tolkachova

Date of interview: July 2003

Leonid Averbuch’s apartment is located in the historical city center of Odessa, in a house built in the 1950s. The apartment is large enough and modestly furnished. In the sitting-room stands a big book-case. There are a lot of books, photos of Leonid from the different periods of his life, card indexes of famous Odessa citizens and chanukkiyah. In the corner near the window is a big writing-desk with a computer on top of it. Leonid is a man of average height, has a bronze sun-tan and a beard that makes him look like a sailor. Despite of his age he is full of energy and strength. Due to his public and literary activities Leonid Averbuch is well-known, not only in the medical circles of Odessa but also in the Jewish community.

Family background

Growing up

During the war

Post-war

Glossary

One of my maternal ancestors Itzhak Zaltzberg was born into the family of Aaron Zaltzberg, a salt miner, who came from the city of Salzburg in Austria to Odessa in 1806. My grandmother Betia Zaltzberg had a copy of the entry in the birth register about Itzhak’s birth, certified by the rabbi of Odessa in 1915. This entry disappeared during the Great Patriotic War 1 when our family evacuated.

Itzhak was my mother’s great-grandfather. His wife Shendel Zaltzberg-Shapiro was born in the town of Akkerman [since 1944 Belgorod-Dnestrovskiy] in 1810. They had eleven children. Two of their sons, Samuel and Wolf, were my great-grandfathers since my maternal grandmother and grandfather were cousins.

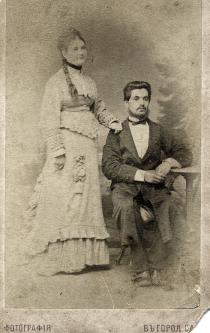

My grandfather Gedali Zaltzberg was born in Odessa in 1865. In winter 1872 his 28-year-old father Samuel Zaltzberg was hit by a horse-drawn sledge. He fell ill, developed galloping consumption and died in the same year. His wife Ita Zaltzberg, the daughter of a wine maker from Odessa called Gluzbar, died half a year after, so deeply struck she was by her young husband’s death. Seven-year-old Gedali became an orphan and his uncle Israel Zaltzberg, who owned a leather raw material supply business in partnership with his brother Wolf, adopted him. Gedali didn’t go to cheder. At the age of ten he went to grammar school. When he was 14 his uncle Israel died of pneumonia. After Israel’s death Gedali went to live with the family of Uncle Wolf, who was a very religious man and wasn’t quite so fond of commerce. Gedali was a business-oriented man. He knew German and French and became the representative of the company. Gradually Uncle Wolf transferred all responsibilities to him. Wolf’s wife Braina even addressed Gedali requesting monthly housekeeping allowances from him. Wolf and Braina had six children; two of them died in infancy. After they died Betia, born in 1875, became the oldest child in the family. Then there were three sons: Israel, Avrum and Moisey. Gedali liked his cousin Betia very much. He prepared her for the Jewish elementary school run by the Reivich sisters that she finished successfully.

In 1888, when Gedali turned 23 and Betia 17, they got married with Wolf and Braina’s consent. They rented apartments in Odessa before the [Russian] Revolution of 1917 2. They lived in the center of town like many families of intellectuals. My grandparents spoke Yiddish, but they also spoke Russian fluently. My grandmother also spoke Ukrainian and my grandfather knew German, French and Polish. Grandfather Gedali didn’t wear payes or a beard. He had a mustache. He liked fancy clothes. My grandfather didn’t wear a kippah at home, but he always wore a hat to go out. He went to the synagogue on holidays. Before the Revolution he often traveled abroad on business.

Before they had children Gedali and Betia visited Palestine. They visited the island Khios, Smirna and Haifa. Grandmother Betia told me a lot about this tour. I even remember the song with which Arabic kids teased travelers from Russia in Haifa, but my grandmother didn’t know the meaning of it. At the end they said ‘Maskok hamzir’ – Russian pig. One of the boys hit my grandmother on her eye with a pickle. My grandmother said they visited a kibbutz and mentioned the name of Belkind. He was probably an activist in the Zionist movement. [Israel Belkind (1861–1929): one of the founders of the pro-Palestinian organization Bilu in Russia, moved to Israel in 1882; got involved in educational activities and founded the first Hebrew school in Yaffa].

My grandmother told me that she was sympathetic with the revolutionary movement and gave shelter to revolutionaries in her apartment in Odessa. The October Revolution didn’t have a major impact on my grandfather’s family since they weren’t rich. After the Revolution my grandfather worked in a supply company, but then he fell ill and remained ill for a long time. My grandfather died of bladder cancer in Odessa in 1933.

After he died Grandmother Betia lived with her sons Wolf and Samuel on the first floor on 19, Kuznechnaya Street in the center of town. They had a well-known neighbor: Maliarov, the former owner and director of the private grammar school that my uncles finished. Every Sunday I went to visit Grandmother Betia. I played in their big yard and the adults could watch me from the window. They had running water and electricity and stove heating. There were five cozy rooms with expensive furniture. I remember a big cupboard with a marble board. There were crystal decanters for strong drinks, cups and wine glasses.

My grandmother was a wonderful housewife. Sometimes they hired housemaids who were usually young girls coming from villages to town to look for a job. My grandmother made delicious Jewish food on holidays – gefilte fish, fluden and strudels with jam, nuts and apples, but they didn’t follow the kashrut. They ate pork. On Sabbath the family had a festive dinner. I remember that there was matzah at Pesach. Grandmother Betia’s birthday was on the day of the first seder [according to the Jewish calendar] and she used to say, ‘My birthday is on the first seder’. There was nothing specifically Jewish in the house; there were no mezuzot on the doors. Grandmother Betia dressed in the fashion of the time. She didn’t wear a kerchief. She spoke Yiddish at home occasionally, but she preferred to read books in Russian. She was well educated and had a thorough knowledge of opera music. They liked music in the family.

My grandmother’s maternal cousin Sophia Wainshtein finished the private music school of Vasilenko in Odessa where she studied playing the piano. She was married to Alexandr Levinson who studied singing in this same school. Sophia accompanied him. Alexandr took on the pseudonym of Davydov. He became a soloist at Mariinskiy Emperor Theater in St. Petersburg. Sophia followed him to St. Petersburg. They had two daughters: Tamara and Tatiana, born before the Revolution. In the middle of the 1920s Davydov moved to Paris where in 1934 he worked with Fyodor Shaliapin [well-known Russian singer (1873-1938)]. In 1936 Davydov returned to the USSR and taught singing in the school of Mariinskiy Theater.

The Davydovs were evacuated to Novosibirsk during the Great Patriotic War. In 1944, when they returned, the family parted: Alexandr Davydov moved to Moscow to the actors-pensioners house and the wife with the daughters went to Leningrad. He hoped to have better conditions in this house. He died there in 1944. His family continued to live in Leningrad. Sophia and her daughters often came to Odessa in summer. My mother and uncle Samuel visited them in Leningrad. Sophia died in the 1950s. I never saw Davydov, but I knew his family very well. His daughter Tamara and I were friends. Tamara died in 1998. She was a master of performing and was awarded the title of ‘People’s Actress’.

During the Great Patriotic War my grandmother was evacuated to Tashkent [3,200 km from Odessa in present-day Uzbekistan] with her son Samuel’s family. When my grandmother was dying in Odessa in 1946 Uncle Samuel, who was an atheist, asked her, ‘Would you like to have somebody recite a prayer at your funeral?’ She replied, ‘No, I don’t want any bought prayers’. Grandmother Betia and Gedali had four children. They were all born in Odessa.

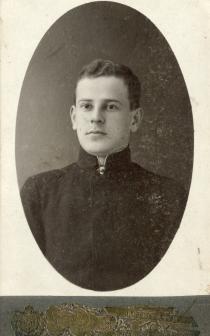

My mother’s older brother Wolf was born in 1894. He finished the private grammar school of Maliarov in Odessa and studied at the Medical Faculty of Novorossiysk University [since 1919 Odessa University]. When World War I began he went to the front. He was shell-shocked and got in captivity. He returned home in 1918. Sometime afterwards he became epileptic. This was a consequence of the shell shock. Uncle Wolf was a doctor. He was single, although he was handsome and a big success with women. He believed he didn’t have the right to marriage due to his illness. Wolf died in evacuation in Tashkent in 1942.

My mother’s other brother Samuel was born in 1897. He also finished the grammar school of Maliarov. Samuel entered the Faculty of Natural Sciences of Novorossiysk University in 1915 and then continued his studies at Kiev Polytechnic College. Once, during the Civil War 3, when he was traveling home from Kiev by train, the train was attacked by Petliura 4 troops. They were looking for Jews, but he managed to hide.

In 1929 the Soviet government sent Samuel to advanced training at Hettingen University and Hanover Polytechnic College in Germany. Samuel was a construction engineer. Before the Great Patriotic War he taught the subject of ‘resistance of material’ at Odessa Industrial College. He married Mina Vysokaya in 1938. She was a lecturer at the Odessa Conservatory. They didn’t have children. During the Great Patriotic War uncle Samuel lectured at Tashkent University, Tashkent Textile College and the Academy of Armored Troops of the Soviet Army. During the war he joined the Communist Party. He knew the theory of Marxism-Leninism well.

In 1949, when he was a lecturer at Odessa Polytechnic College, Uncle Samuel was accused of cosmopolitism [see campaign against ‘cosmopolitans’] 5. I was waiting for him in the hallway of the conference-room where a meeting took place. The subject of the meeting was my uncle’s ‘case’. His friends and students spoke at the meeting criticizing my uncle. Later they apologized and confessed to him that they had been acting against their will. It was true because if they had refused to speak against him they would have had to share his fate. After the meeting I accompanied my uncle to his home. He didn’t speak on the way, but when we arrived at his place he said, ‘Well, I should expect an arrest now, I suppose’. He was so shocked that he went to bed in his clothes and shoes. He slept 48 hours. Later he went to the Central Committee of the CPSU in Moscow. He managed to resume his membership in the Party, but not his job. He moved to Penza, where he worked at Penza Industrial College, and then to Kishinev, where he was also a lecturer. He returned to Odessa in the 1960s after he retired. My uncle was a communist, but these events left a deep imprint on his heart. Samuel’s wife Mina died in 1977. Uncle Samuel lived the rest of his life with me. He died in

1986. We buried him in the Tair cemetery [the town cemetery] in Odessa.

My mother’s younger sister Ida Zaltzberg was born in 1901. She studied at Odessa Conservatory with Oistrach and Dankevich. [Editor’s note: David Oistrach (1908–1974): Soviet violinist, pedagogue, one of the greatest musicians of the 20th century; Konstantin Dankevich (1905–1984): popular Soviet composer, pianist and pedagogue. He taught in Odessa and Kiev Conservatories. In 1984 Odessa Music School was named after him.] Then she worked in the music school at the House of Scientists in Odessa. I remember my parents took me to her classes. In my memory Aunt Ida is a beautiful, well-dressed and bright woman. I associate her with the first symphonic concert in the Odessa Philharmonic that I went to. Her former fellow student Konstantin Dankevich was a conductor. After the concert he came to see us. He threw me in the air. He was a very tall man. I was about four years old then. Ida’s husband Moisey Barero, a Jewish man, had a daughter from his first marriage. Ida didn’t have children of her own. In 1941 Ida, her husband and her stepdaughter were killed in the ghetto in Odessa. She was 40 years old.

My mother Malka Zaltzberg was born in 1899. She studied at the Liberson private grammar school. The director of this school was a relative of ours. Later she studied at the grammar school of Shyleiko and Richter. My mother didn’t get any Jewish education at home. She was the peacemaker in the family – she always smoothed conflicts between family members. In 1919 my mother finished a six-month course of medical nurses and entered the Medical Faculty of Novorossiysk University. She graduated in 1922. She became a doctor at the central tuberculosis outpatient clinic called White Flower. Later this clinic joined the Odessa Scientific Research Institute of Tuberculosis.

My paternal great-grandfather Mordko Goldshtein came from Bogopol’. [Editor’s note: Bogopol’ was a Jewish town in Baltskiy district in Podolsk province. At the end of the 19th century 5,909 of 7,226 inhabitants of Bogopol’ were Jews.] He had five children: two sons, Abram and Haskel, and three daughters. There were different stories told in our family about the life of his older daughter Rachel, born in 1855. She was married to a big businessman in Kiev called David Benderski. I remember one of those stories. David had a lover who was a seamstress. He bought her an apartment. It happened so that he died when he visited her. This seamstress called my aunt to inform her on what had happened. My aunt went to the house of her husband’s lover with two broad-shouldered clerks of her husband. Those clerks carried her husband out of the house pretending that he was dead drunk. In the same way they took him into his bedroom. Rachel managed to prevent a public scandal by this smart conduct and plotting. There were two other daughters besides Rachel: Lisa, born in 1856, her name in marriage was Sher, and my grandmother Esther, born in Bogopol’ in 1854. My grandmother got married in 1885.

My paternal grandfather Leib Averbuch was born in Kishinev in 1865. My grandfather studied in cheder. After they got married my grandparents settled down in Bogopol’. Grandfather Leib was a senior man at the synagogue. He didn’t have any other job. My grandmother was the breadwinner in the family; she lent money to Christians. They were very religious and spoke Yiddish at home. Grandfather Leib wore a beard and mustache. He didn’t have payes, but he had whiskers. He wore a hood and a yarmulka in the synagogue. That’s what my father told me; I didn’t know my grandfather personally. He died in 1905 in a fire accident at the age of 40. He was asleep when his house caught fire. He must have suffocated in the smoke. I don’t know where the other members of the family were at that moment.

After this accident, the family moved to Odessa. I don’t know what made them move. I know that my grandmother and her children lived on Avcinnikovski Lane in the center of town. My grandmother’s brothers supported her. Before the Revolution they leased fields and were better off than my grandmother. Uncle Abram, born in 1952, had fancy clothes and looked like an aristocrat. He was very tidy and staunch. My parents believed that after the Revolution Uncle Abram lived on the money that he managed to hide from the expropriation by the Soviet authorities. Uncle Abram was married. He died in his late 60s, before the Great Patriotic War. Uncle Haskel made the impression of a sloppy and quarrelsome man. He had two daughters who lived in Leningrad. He became a widower before the war. He perished in Odessa ghetto in 1941.

My grandmother had two sons and two daughters. My father’s younger brother Haskel Averbuch was born in 1890. He finished a private drama school in Odessa. He was fond of acting. During World War I Haskel was recruited to the army at the age of 24. He was awarded two St. George Crosses 6 of the 3rd and 4th grades and a St. George medal. After the February Revolution Haskel took part in a congress of veterans of the war. He met A. F. Kerensky 7 at this congress. When Kerensky came on a visit to Odessa in May 1917 Uncle Haskel served as a mission officer for him. Kerensky solicited for his promotion to an officer’s rank and he became an ensign. After the October Revolution Haskel joined the Bolsheviks and was chief of militia in Odessa. When Denikin 8 troops entered Odessa he was arrested and sentenced to death for cooperation with the Soviet power. He was executed on 28th September 1919. My grandmother Esther kept some insignia of his officer’s valor: his dagger, orders and a medal, but she destroyed them in 1937 [during the Great Terror] 9.

My father’s younger sister Rosa, born in 1892, was raised in the family of her mother’s childless sister, Rachel Benderskaya, in Kiev. Rosa would have become the heir of a significant fortune of the Benderskiy family, if it hadn’t been for the October Revolution. The family’s property was expropriated by the Soviet authorities. Rosa finished the Medical Faculty of Novorossiysk University and married Konstantin Chertkov who came from a well-known Russian family of merchants in Odessa. Aunt Rosa and her husband left for Moscow in the 1930s. Her husband worked as an advisor at the Ministry of River Transport of the USSR, Aunt Rosa was a doctor, a throat specialist. They didn’t have children. Rosa’s husband died in the late 1960s. Aunt Rosa died at the age of 92 in 1984.

My father’s second sister Tsylia was born in 1896. She was a pharmacist. She lived in Odessa, was single and had no children. During the Great Patriotic War she was in evacuation in Tashkent with us. At the end of her life Aunt Tsylia moved to her older sister Rosa in Moscow. She died in 1956.

My father Grigori, his Jewish name was Gershon, was born in Bogopol in 1888. Like all other Jewish boys he studied in cheder. When his family moved to Odessa he became an apprentice to a pharmacist. It was a popular profession among Jews since it gave them the right to live beyond the [Jewish] Pale of Settlement 10. He finished the extramural Faculty of Chemistry and Pharmacy and was the director of a pharmacy at the same time. In 1927 my father received an apartment on Preobrazhenskaya Street in the center of town. It was a communal apartment 11. There was another Jewish family that lived in this apartment: the family of doctor Moisey Finegold. My father lived in this apartment with Grandmother Esther and his sister Tsylia.

My parents were introduced to one another by their relatives. My father was eleven years older than my mother. My mother was 27 at the time. They went to the theater together. My mother worked and didn’t allow my father to pay for her tickets. My parents got married in Odessa in 1927. They had a civil wedding. There was no chuppah. Theirs was a pre-arranged marriage that grew into a solid reliable relationship. After they got married the newly-weds settled down in my father’s apartment on Preobrazhenskaya Street. The house where they lived belonged to an insurance company called Russia before the October Revolution.

We had four rooms in this apartment: my parents’ bedroom, were I slept as well, my grandmother’s room, my aunt Tsylia’s room, and a small room near the kitchen where the housemaid lived. The Russia insurance company provided furniture for our apartment before the Revolution. It was stylish mahogany furniture decorated with bronze. I remember a big mirror with a glass table, a low table and armchairs. My grandmother had an ancient chest of drawers in her room and an oak folding table. There were beautiful chairs with carved chair-backs. There were Moldavian carpets on the floors. After 1939 we got a radio set. There was a bathroom in this apartment, but my family didn’t use the bathtub since it was a communal apartment. I remember when I was small I was washed in a basin and when I grew older my father took me to the sauna. Most of our neighbors were Russian. The relationship between the neighbors was friendly enough and very reserved.

I was born on 31st October 1930. I remember well my nanny Olesia, a nice and caring old Ukrainian woman. I use to put my head in her warm jacket feeling very comfortable. She left when I turned three years old and our housemaid Irina Bessarab looked after me. I associate Irina with the famine of 1933 12. In 1933 Irina came from a village. She was thin and had her hair shaved since she had typhoid. She was taken to the kitchen. All she could say was, ‘Madam, may I have something to eat?’ Only after she had had some food, she could speak properly. She became a beautiful full-bodied woman. When she got married she lived in our apartment with her husband for some time.

I didn’t go to kindergarten. I studied with a teacher who had a Froebel 13 diploma; there were graduates of this institute in Odessa. Many of them knew foreign languages and taught children to speak a foreign language. My teacher Polina Ianovna Galka didn’t know any foreign languages, but when she fell ill or went on vacation we had a replacement, Victoria Georgiivna Moskalyova, who taught me French. There were seven other children in my group. This group gathered at the teacher’s home. We, children, brought our breakfast with us. We went for a walk on Primorski Boulevard or to Teatralnaya Square, or the Palais Royal [this is how Odessites call the garden near the Odessa Opera House], or Gorodskoy garden. Then we went to her house, where we had our breakfast, played games and learned to read.

I went to Novy Market with Grandmother Esther who bought kosher food products for herself. I remember my grandmother Esther well. She dressed like all other women in town. She wore long dark skirts and dark shirts. In winter she wore woolen clothes and in summer a fustian. She never wore light colors and even at home she wore a kerchief. Grandmother Esther didn’t quite have political preferences, but since her favorite younger son was shot by Denikin troops she hated all Whites 14; however, this doesn’t mean that she favored the Reds 15.

Grandmother Esther observed the kashrut. She didn’t trust my mother or the housemaid to prepare food for her. She bought her quarter of a chicken from one and the same seller, I think. Frau Frieda, a German milkmaid, delivered dairy products to our house. She came from Grossliebental, a German colony 16 near Odessa. Early in the morning, at 7am, she already knocked on the backdoor. When asked, ‘Who’s there?’ she replied, ‘Frau Frieda, I’ve got milk for you’. She wore a checkered kerchief. She had a big milk can from where she poured milk with a big mug that had a long handle. At times poultry tradesmen came to the yard shouting, ‘Want a chicken? Quarter chicken or chicken legs?’ There was a period before the war when there weren’t enough food products and bread was sold in limited quantities. Each family left a linen bag with a name at a store and then these bags were delivered on carts to the houses. The tenants came outside to pick up their bags. There was a bread rate per person. It wasn’t a famine because there was enough bread being delivered. There was a period when there was no sugar in stores and people bought caramel candy instead.

My parents treated each other with love and respect. After my father finished the Chemistry Engineering Faculty of the Industrial College in 1936 he worked as a chemical engineer at food enterprises in Odessa. I don’t remember the specific companies he worked for. My mother worked as a doctor at Odessa Scientific Research Institute of Tuberculosis. My parents worked a lot. They liked to spend their evenings with the family. We were doing all right, though we couldn’t afford any luxuries. My parents went to the theater and visited friends. Most of their friends were Jewish, but my mother also had non-Jewish friends. At home my parents spoke Russian and only switched to Yiddish when they didn’t want me to understand the subject of their discussion. My father spoke fluent Yiddish, but my mother didn’t know it quite so well. So when they switched to Yiddish my father teased her a little about the mistakes she made.

Both my grandmothers told me something about Jewish traditions, but I took it as a vestige of the past. I didn’t make this particular point to them, but I thought it was something that had nothing to do with me. Every Friday evening Grandmother Esther covered the table in her room with a yellow tablecloth and invited us to dinner. Her brother Abram and Haskel visited my grandmother on this day. They were almost the same age and often quarreled and Grandmother Esther had to help them to make it up. By next Saturday they were arguing again. My grandmother observed Sabbath. She didn’t go to the synagogue when I remember her, because she was very old.

My grandmother had religious books. She prayed from the siddur, read the Torah in Hebrew regularly and knew the weekly sections by heart. [Editor’s note: The Torah is divided into 54 parts; one is to be read each Sabbath. Two such parts are sometimes read on a single Sabbath; otherwise the cycle could not be completed in one year.] My father was an atheist, but I remember clearly that on one of the Jewish holidays – it may have been Yom Kippur – he put on his fancy suit and a dark hat and went to the synagogue. I don’t know what synagogue my father attended, but I think there was only one synagogue in Odessa at the time.

We didn’t have a big collection of books at home, but in our family we read a lot. There were subscription editions before the war and we had books by Balzac, Maupassant, Pushkin 17 and Lermontov 18. My father was very fond of Lermontov and often sang ballads using his lyrics. I was also good at literature for a boy of ten. My parents took care of what I read. They brought me books to read. I read books by Soviet children’s authors: Chukovskiy, Marshak 19 and Mikhalkov. Later I got the History of Animal World by Brehm. I took to liking adventure stories. Later my parents enrolled me on the list of readers in the library of the House of Scientists. My parents also went to the town library: my mother went there to prepare her dissertation and my father went there every now and then. My mother knew three foreign languages and my father knew two. My parents subscribed to the Bolshevik’s Banner communist newspaper.

Every summer our family rented a dacha [cottage] at the seashore. In 1938 Uncle Samuel built a dacha and we stayed there all together. When I was small we traveled to the dacha on a horse-drawn cart. I sat beside the balagula [coachman] on his seat and several times I even used the whip on the horse. Later we had our luggage transported on a truck and I used to sit in the cabin. I also remember how the husband of my mother’s friend Bella Goldman Rovinski, a Jew, deputy chief of the regional military hospital, gave us a lift in his cabriolet with a convertible tarpaulin top on their twin daughters Lilia and Maya’s birthday.

I remember people speaking in a whisper about the arrests in 1937. One of my parents’ closest friends, doctor Yakov Kaminski, was arrested in 1937. His wife Vera knocked on our door at 7 o’clock in the morning and asked us if she could stay with us for a while since her husband Yakov had been arrested. She had made the rounds of several of their acquaintances, but they didn’t even open their doors to her. My parents let her in, gave her a cup of tea and tried to console her. In the evening my father took her to her home. They supported her throughout Yakov’s time in exile, which lasted 20 years, and when he returned they remained friends. In 1938 my grandmother Betia’s brother Avrum Zaltzberg was arrested and executed without even a trial or investigation. In the same year my grandmother Esther died and was buried in the 3rd Jewish cemetery. We didn’t find her grave after the war. I guess it had been destroyed.

I turned eight in 1938 and my father took me to submit my documents to school in August. The director of the school, Riabukha, tested every child. Since I could already read and write and knew poems by heart he enrolled me in the 2nd grade. In January 1939 Riabukha was shot for deviations from the Party policy in the field of education. I liked to study. In the 3rd grade I was even awarded a diploma for my school successes. My first teacher was Maria Dmitrievna Dorokholskaya. We all liked her a lot. We also liked Valentin Alexandrovich Zhukov, our teacher of physics. He took part in the Spanish Civil War 20. He wore a Navy jacket and had an Order of Honor. Olga Moiseyevna Erlich was our teacher of rhythmic and singing. We sang in a choir and played in a so-called noise orchestra: we played castanets, triangles, etc. We often had morning concerts at school where we sang, recited poems and gave amateur performances. My father took me to the navy club in the Town House of Pioneers.

There were many Jewish children at school. I remember Bernard Shchurovetski. He was one year my senior. I remember him running ahead of a group of boys waving his hand as if he was holding a sable shouting, ‘Follow me, Jewish battalion!’ In 1948 he was arrested for Zionism when he was a student of Odessa University. He was sentenced to ten years in prison. As for the prewar period I want to say that the notion of the Soviet people wasn’t something abstract. It had its grounds. I never faced any anti-Semitism before the war, although we made quite clear the nationality we belonged to.

I met my schoolmates after school. We played the ‘cossacks and bandits’ game [an equivalent of ‘Cowboys and Indians’] and football, mostly with balls made out of cloth. We also played ‘mayalka’ tossing up a bag filled with millet or sand. The one that tossed it up for the longest time won. I also had friends in the yard. We played a stick game. There was a wooden stick and a board – a bat. We drew a circle and put the stick in the middle. Then we hit on its edge with a bat and when it popped up we had to throw it with the bat as far as possible.

I had a friend whose name was Ivetta. She was the daughter of our co-tenants, the Finegolds. She was three years older than I and had a big influence on me. Ivetta played the piano and I danced to this music with her friends or we danced to the radio. I fell in love with all her friends in a row. We played this bottle game: We stood in a circle and twirled a bottle in the middle. Then the two that the neck and bottom of the bottle pointed at kissed.

On weekends my parents and I went for a walk and to the theater. They took me to children’s performances at the Tyuz theater [theater for young audiences in the USSR], the Opera, the Philharmonic, and to symphonic orchestras. We often went to the cinema where we watched Soviet films. My father spent more time with me than my mother did. My favorite holidays were 1st May and October Revolution Day 21.

My father and I went to parades, bought flags and balloons. In the middle of the 1930s people began to celebrate New Year and decorate trees. At first Soviet authorities forbade Christmas trees since it was considered to be a religious Christian tradition. There were also so-called ‘fore post clubs’ when children got together in a room or hall in the district where they lived. We had concerts and other events there and played games.

My mother had a few relatives in America. One of them was my grandmother Betia’s brother Israel Zaltzberg. Uncle Israel was a communist in America, but he owned a factory. He visited Odessa in 1935. He visited my grandmother in her apartment in Kuznechnaya Street. There was a reception and there were photographs taken. He brought me some gifts. Our relatives corresponded with him before his arrival, but after he left all such contacts were kept secret since it became dangerous to disclose them [it was dangerous to keep in touch with relatives abroad] 22.

In 1939 Soviet troops came to Western Ukraine and Western Belarus. My father was recruited to the army and took part in those campaigns. The beginning of the war in 1939 was practically not discussed by the mass media. Sometime before it, the USSR entered into the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact 23 with Germany. I remember the German Consulate in Odessa on the corner of Petra Velikogo and Sadovaya Street and two big red banners with white circles and black swastikas on them.

I was ten when the Great Patriotic War began on 22nd June 1941. My father was assigned to a military unit and although he had had myocarditis some time before and was 53 years old he joined this unit. When my mother mentioned that he could probably do something to avoid going to the front he replied that when fascists attacked the country a Jewish man had to be in the armed forces. He left that same day and never returned. This was at least the fourth war in his life. He went to the front-line forces in Bessarabia 24.

He served in a medical unit of Primorskaya army and was responsible for logistics supplies to medical institutions and subdivisions of Primorskaya army in Sevastopol. He perished there during the defense of Sevastopol in July 1942. I still have 16 letters that he wrote from the front.

In July 1941 my mother, Aunt Tsylia and I evacuated from Odessa. We went to Novorossiysk [700 km to Odessa by sea] by the military boat Dnepr. From there we took a train to Krasnodar – this was my first train trip. We got off at Zatoka station in Stanitsa Slavyanskaya on the way to Krasnodar. We got accommodation with a Kazak family, the Kulikovs. They didn’t care what nationality we belonged to. They treated us as if we were their family. They shared their food with us. Then we went to Rostov where we reunited with Uncle Samuel, his wife, grandmother Betia and Uncle Wolf. We went to Kalach by boat along the Don River, from there we took a train to Stalingrad, then we went to Kuibyshev down the Volga and from there we took a train to Tashkent.

In evacuation my mother was the manager of the X-Ray department at the Institute of Tuberculosis in Tashkent. In 1943 she defended her dissertation for the title of candidate of medical services and in 1947 she was awarded the title of senior scientific employee. I went to the 5th grade at school in Tashkent. In a year we moved to another district and I finished my 6th and 7th grades in another school. My classmate Lyonia Yusupov – his mother was Russian and his father was Uzbek and was the First Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist party of Uzbekistan – helped me to get a recommendation from his father to join the Komsomol 25. I became a Komsosol member in 1944 before I turned 14. In August 1944 during my vacations I began to work as a medical statistics specialist in the institute where my mother worked.

Before the war I didn’t face anti-Semitism except for the word ‘zhyd’ [kike] that I heard several times, but during the war there was open anti-Semitism. It was intertwined with the hatred to people in evacuation. The local Russian population, Russian people who were in evacuation in Tashkent and Uzbeks demonstrated it. Uzbeks knew the word ‘yakhuda’ [Jew in Arabic] and even at the market when a Jewish customer tried to bargain with them they said ‘Jebrei’ [mispronunciation of Jew], go away and come back tomorrow’. Once a group of local boys brutally beat me up, kicking me with their feet on my face and calling me ‘zhydowskaya morda’ [a Jewish mug].

I went to the synagogue for the first time in Tashkent in 1944. There was a meeting with a former inmate of the Warsaw ghetto who had managed to escape. My uncle Samuel took me there. On our way to the synagogue he told me a little about Jewish traditions. I cannot remember the details of what this man told the audience. He spoke German and there was an interpreter. [Editor’s note: this man most likely spoke Yiddish and not German.] My uncle Wolf died of a brain tumor in Tashkent. I heard the mourning prayer recited by a man from the synagogue for the first time in my life at his funeral.

We returned to Odessa in October 1944 with the Odessa flour grinding factory. We arrived at Odessa-Malay station and from there we were taken to the hostel of the flour-grinding factory by truck. During the war Dumitrasku, the editor of the Russian weekly newspaper Molva, lived in our apartment on Preobrazhenskaya Street. When we returned it was inhabited by comrade Melnichenko, the chairman of the water transport district council. He occupied all six rooms of our apartment, although two families had lived in the apartment before the war. When the Finegold family – our co-tenants – arrived, Melnichenko did us a big favor: he vacated two rooms for their family and two rooms for us. He stayed in our apartment for quite a while. Actually all our belongings were gone. After returning to Odessa Grandmother Betia lived with us. She died in 1946. She was buried in the Jewish section of the second international cemetery. No Jewish rituals were followed.

I went to the 8th grade when we returned to Odessa. It was a different Odessa and so was I. I had new friends at school. I had many Jewish classmates. The director of the school Osip Semyonovich Stoliarski was a Jew. There were many Jewish teachers. There was anti-Semitism in postwar Odessa. Probably people contracted it from the fascists during the occupation. I often heard people say, ‘The Jews are back telling us what to do’.

In 1946 I entered Odessa Medical College. Since I was under 16 and didn’t have a passport I was admitted as a candidate student and was enrolled only after I obtained my passport. There was no anti-Semitism in college. There were many Jews in college: veterans of the war, mature people. I was an active Komsomol member and a member of the Komsomol committee of the college. In 1949, when I was a 4th-year student I married my co-student Sophia Rudman. She was a very interesting person. She was very musical, had the best marks in gymnastics and was a great success with young men.

Sophia was born in Odessa in 1928. During the war she was in evacuation in Tokmak, Kyrgyzstan, with her mother. Sophia is a Jew. Her grandfather lived in Moldavanka 26 where Jews lived in their own neighborhood and observed Jewish traditions. Sophia’s mother knew a little Yiddish and was a very sociable woman. She kept in touch with her Jewish surrounding. We didn’t observe the Jewish holidays in our family, but we bought matzah at Pesach. My wife’s mother could even make it. Basically, we didn’t observe any Jewish traditions or the kashrut.

In my 6th year of studies I began to specialize in lung diseases. After finishing college in 1952 my wife and I got a [mandatory] job assignment 27 to the village of Malorita in Brest region, Belarus, where we worked as phthisitricians. In 1952 during the time of the Doctors’ Plot 28 I got into trouble. Phthisitricians use to get into this trap. I treated my patients with pneumothorax. During this procedure an air bubble may get into a vein. If it gets into a venous vessel it may cause embolism. One of my patients – the agronomist Nikolay Misyuk had brain embolism once. I remember that in his case I had to fix his head in the lowest position with his feet up to force this air bubble out. I did this and he recovered, but he had hemorrhage in his retina. Nikolay appreciated what I did for him, but his wife wrote a letter to the prosecutor’s office complaining that Jewish doctor Averbuch wanted to kill her husband, an agronomist, to cause damage to the socialist agriculture. I was called to the prosecutor’s office where they had a talk with me, but at some point of time it all ended. When we were leaving Malorita we already knew that this Doctors’ Plot was just that. Stalin had died by then. His death was a hard blow. Besides, we were afraid that the new leadership of the country would strengthen its dictatorship. I dedicated one of my poems to Stalin’s death.

In 1953 I entered the clinical residency at the Institute of Advanced Training of Doctors in Minsk. My tutor was Professor Agranovich. Simultaneously I studied at the extramural postgraduate school in Moscow where my tutor was Alexandr Rabukhin, one of the biggest phthisitrician in Kiev. He was also a Jew. There were many Jewish doctors in the USSR while in phthisiology almost all of them were Jews. It was a difficult profession, but Jews wanted to have it.

Our daughter Irina was born in 1953. In 1955 my wife and I returned to Odessa where we rented an apartment, and we often went to see my mother. After my father’s death my mother didn’t marry again. She went on to work as a phthisitrician. She died in 1989 at the age of 90 and was buried in the international cemetery of Odessa.

After returning to Odessa I began to write my dissertation. Simultaneously I lectured at Odessa Medical College. My tutor made it clear to me that I didn’t have a chance to keep a job at the college because of my Jewish nationality. In January 1959 I began to work as a registrar at the regional tuberculosis outpatient clinic. I was appointed its manager in July of the same year. I often traveled on business to Ukrainian towns, Moscow and Leningrad.

I began to travel abroad in 1960. Those were countries of democracy: Hungary, Romania and Bulgaria. When I visited Hungary in the 1960s I understood how serious events were during the Revolution of 1956 29, what tragedy it had been for the people of Hungary and what the real role of the USSR had been. About the events in Czechoslovakia in 1968 [Prague Spring] 30 I remember that we listened to foreign radio stations. We understood that it was a blood-shedding suppression of the people’s movement. My friends and I had a negative attitude towards this.

We lived a stable and wealthy life. We communicated with Uncle Samuel and Aunt Rosa who lived in Moscow, and Lida, the daughter of Avrum Zaltzberg. We got together on birthdays or Jewish holidays. In summer we stayed at the dacha. Our son Grigori was born in 1965. My children always knew that they were Jews and identified themselves as Jews. However, they didn’t get any Jewish education. My children knew about the Holocaust and about members of our family who had perished in the ghetto and about their grandfather who had perished at the front.

Our daughter Irina studied in a secondary and a music school. She was a concertmaster and took part in concerts with children’s groups. After finishing school she finished the Music College in Vitebsk since it was difficult for a Jewish girl to enter the Music College in Odessa. After finishing this College Irina was the manager of a band that worked on a cruiser. She was also a soloist and played keyboard. Irina married a Russian man, Alexandr Rakov, a musician. In 1978 they moved to Australia. I cannot say that I was happy when my daughter left. I wasn’t sure whether it was the right decision, but it turned out it was. They live in Sidney where they opened a computer design company. Irina is a musician there. Their daughter Caroline was born in 1979. She finished a technical college in Sidney. Her specialty is computer graphics. I visited them in 1991. It was a wonderful trip and a happy meeting with my darling daughter and granddaughter Caroline.

Sophia and I divorced in 1968. Two years later Sophia married a Russian man. Since her second husband was Christian they celebrated Christian and Jewish holidays. They made Easter bread and painted eggs at Easter. They also observe Jewish holidays, but without strictly following all traditions. My son Grigori lived with his mother. He identifies himself as a Jew, although he is not even circumcised. Grigori finished school in 1972 and then studied at the Faculty of Physical Education of Odessa Pedagogical College. After his 4th year in college he was recruited to the army. He served in anti-missile troops in Zaporozhye. After his army service Grigori worked in a children’s home and then was a teacher of physical education at school. In 1991 he moved to Australia, to his sister Irina. He lives in Sidney and works as an assistant doctor.

I married Irina Chaikovskaya in 1969. Irina is Ukrainian. She was born in Vinnitsa in 1938. During the war she was in evacuation in Tashkent with her mother. My second wife finished the Faculty of Philology of Odessa Pedagogical College and the Faculty of Defectology of Moscow Pedagogical College. She is a speech specialist and an Honored Teacher of Ukraine. [Editor’s note: Honored Teacher of Ukraine is a state award.] We’ve been married for over thirty years now.

The 1970s were stable years in our country: no arrests or suppression. We were wealthy and had many opportunities to spend our spare time as we liked. My wife and I read a lot, went to the theater and symphonic music performances. Famous musicians and the best theater groups of the USSR often came on tour to Odessa. In the 1970s there was more space for criticism of the government. My professional life has always been the focus of my life. I was the manager of the tuberculosis clinic for 44 years. I was also involved in scientific activities. I have over 65 publications and one monograph. In 1994 I was awarded the title of candidate of medical sciences based on my scientific work. I have never been a party member.

In 1967 during the Six-Day-War 31 and in 1973 during another war [the interviewee is referring to the so-called Yom Kippur War] 32 I felt pain in my heart and wished victory for Israelites. I was terribly upset about the termination of diplomatic relationships of the USSR with Israel. I was convinced that it was a mistake of the Soviet government. I felt like protesting against the USSR’s support of the enemies of Israel. I always felt great interest in Israel. I always wanted to visit there and was very happy when I got an opportunity to do so in 1999. I admired the country and felt proud for the people. I sympathized with those that were moving to Israel, but I never considered this option for myself.

When perestroika 33 began in 1986 I had hopes that they would build socialism with a human face. I need to say at this point that I still feel sorry that socialism is a utopia. I’m really sorry that such is reality. This utopia is even more dangerous since it is so attractive.

The Jewish life has revived in Odessa. In 1997 I became a volunteer and member of the Board at the Jewish charity organization Gmilus Hesed. During this period I turned to Judaism to learn more about traditions and the history of the Jewish people. I remain agnostic to a certain extent. I’m not a religious Jew who goes to pray at the synagogue every day. I don’t follow the kashrut either, but I greatly respect the Jewish traditions. I know a lot more about the traditions and history of my people now and this gives me the feeling of solidarity with my people.

I go to the synagogue on high holidays. I take part in charity events. I’m the Deputy Chairman of the Board of Gmilus Hesed. I write in Russian for the Jewish newspapers Or-Sameah and Shomrei-Shabbos and the magazine Migdal Times. I write articles on Jewish subjects as well. I collect and publish materials about famous Odessites. I give lectures about outstanding Jewish Odessites and the history of anti-Semitism at the Open Jewish University at the educational center Moria. I write poems and prose. Some Odessa publishing houses published my volume of poems and a book of memoirs about Odessa and Odessites. Besides, my book about Jews who worked for the Soviet intelligence service has been published in two editions.

1 Great Patriotic War

On 22nd June 1941 at 5 o’clock in the morning Nazi Germany attacked the Soviet Union without declaring war. This was the beginning of the so-called Great Patriotic War. The German blitzkrieg, known as Operation Barbarossa, nearly succeeded in breaking the Soviet Union in the months that followed. Caught unprepared, the Soviet forces lost whole armies and vast quantities of equipment to the German onslaught in the first weeks of the war. By November 1941 the German army had seized the Ukrainian Republic, besieged Leningrad, the Soviet Union's second largest city, and threatened Moscow itself. The war ended for the Soviet Union on 9th May 1945.2 Russian Revolution of 1917

Revolution in which the tsarist regime was overthrown in the Russian Empire and, under Lenin, was replaced by the Bolshevik rule. The two phases of the Revolution were: February Revolution, which came about due to food and fuel shortages during World War I, and during which the tsar abdicated and a provisional government took over. The second phase took place in the form of a coup led by Lenin in October/November (October Revolution) and saw the seizure of power by the Bolsheviks.3 Civil War (1918-1920)

The Civil War between the Reds (the Bolsheviks) and the Whites (the anti-Bolsheviks), which broke out in early 1918, ravaged Russia until 1920. The Whites represented all shades of anti-communist groups – Russian army units from World War I, led by anti-Bolshevik officers, by anti-Bolshevik volunteers and some Mensheviks and Social Revolutionaries. Several of their leaders favored setting up a military dictatorship, but few were outspoken tsarists. Atrocities were committed throughout the Civil War by both sides. The Civil War ended with Bolshevik military victory, thanks to the lack of cooperation among the various White commanders and to the reorganization of the Red forces after Trotsky became commissar for war. It was won, however, only at the price of immense sacrifice; by 1920 Russia was ruined and devastated. In 1920 industrial production was reduced to 14% and agriculture to 50% as compared to 1913.4 Petliura, Simon (1879-1926)

Ukrainian politician, member of the Ukrainian Social Democratic Working Party, one of the leaders of Centralnaya Rada (Central Council), the national government of Ukraine (1917-1918). Military units under his command killed Jews during the Civil War in Ukraine. In the Soviet-Polish war he was on the side of Poland; in 1920 he emigrated. He was killed in Paris by the Jewish nationalist Schwarzbard in revenge for the pogroms against Jews in Ukraine.5 Campaign against ‘cosmopolitans’

The campaign against ‘cosmopolitans’, i.e. Jews, was initiated in articles in the central organs of the Communist Party in 1949. The campaign was directed primarily at the Jewish intelligentsia and it was the first public attack on Soviet Jews as Jews. ‘Cosmopolitans’ writers were accused of hating the Russian people, of supporting Zionism, etc. Many Yiddish writers as well as the leaders of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee were arrested in November 1948 on charges that they maintained ties with Zionism and with American ‘imperialism’. They were executed secretly in 1952. The anti-Semitic Doctors’ Plot was launched in January 1953. A wave of anti-Semitism spread through the USSR. Jews were removed from their positions, and rumors of an imminent mass deportation of Jews to the eastern part of the USSR began to spread. Stalin’s death in March 1953 put an end to the campaign against ‘cosmopolitans’.6 St

George Cross: Established in Russia in 1769 for distinguished military merits of officers and generals, and, from 1807, of soldiers and corporals. Until 1913 it was officially referred to as Distinction Military Order, from 1913 as St. George Cross. Servicemen awarded with St. George Crosses of all four degrees were called St. George Cavaliers.7 Kerensky, Aleksandr Feodorovich (1881-1970)

Russian revolutionary. He joined the Socialist Revolutionary Party after the February Revolution of 1917, that overthrew the tsarist government, and became Minister of Justice, then War Minister in the provisional government of Prince Lvov. He succeeded (July, 1917) Lvov as premier. Kerensky's insistence on remaining in World War I, his failure to deal with urgent economic problems (particularly land distribution), and his moderation enabled the Bolsheviks to overthrow his government later in 1917. Kerensky fled to Paris, where he continued as an active propagandist against the Soviet regime. In 1940 he fled to the United States.8 Denikin, Anton Ivanovich (1872-1947)

White Army general. During the Russian Civil War he fought against the Red Army in the South of Ukraine.9 Great Terror (1934-1938)

During the Great Terror, or Great Purges, which included the notorious show trials of Stalin's former Bolshevik opponents in 1936-1938 and reached its peak in 1937 and 1938, millions of innocent Soviet citizens were sent off to labor camps or killed in prison. The major targets of the Great Terror were communists. Over half of the people who were arrested were members of the party at the time of their arrest. The armed forces, the Communist Party, and the government in general were purged of all allegedly dissident persons; the victims were generally sentenced to death or to long terms of hard labor. Much of the purge was carried out in secret, and only a few cases were tried in public ‘show trials’. By the time the terror subsided in 1939, Stalin had managed to bring both the Party and the public to a state of complete submission to his rule. Soviet society was so atomized and the people so fearful of reprisals that mass arrests were no longer necessary. Stalin ruled as absolute dictator of the Soviet Union until his death in March 1953.10 Jewish Pale of Settlement

Certain provinces in the Russian Empire were designated for permanent Jewish residence and the Jewish population was only allowed to live in these areas. The Pale was first established by a decree by Catherine II in 1791. The regulation was in force until the Russian Revolution of 1917, although the limits of the Pale were modified several times. The Pale stretched from the Baltic Sea to the Black Sea, and 94% of the total Jewish population of Russia, almost 5 million people, lived there. The overwhelming majority of the Jews lived in the towns and shtetls of the Pale. Certain privileged groups of Jews, such as certain merchants, university graduates and craftsmen working in certain branches, were granted to live outside the borders of the Pale of Settlement permanently.11 Communal apartment

The Soviet power wanted to improve housing conditions by requisitioning ‘excess’ living space of wealthy families after the Revolution of 1917. Apartments were shared by several families with each family occupying one room and sharing the kitchen, toilet and bathroom with other tenants. Because of the chronic shortage of dwelling space in towns communal or shared apartments continued to exist for decades. Despite state programs for the construction of more houses and the liquidation of communal apartments, which began in the 1960s, shared apartments still exist today.12 Famine in Ukraine

In 1920 a deliberate famine was introduced in the Ukraine causing the death of millions of people. It was arranged in order to suppress those protesting peasants who did not want to join the collective farms. There was another dreadful deliberate famine in 1930-1934 in the Ukraine. The authorities took away the last food products from the peasants. People were dying in the streets, whole villages became deserted. The authorities arranged this specifically to suppress the rebellious peasants who did not want to accept Soviet power and join collective farms.13 Froebel Institute

F. W. A. Froebel (1783-1852), German educational theorist, developed the idea of raising children in kindergartens. In Russia the Froebel training institutions functioned from 1872-1917 The three-year training was intended for tutors of children in families and kindergartens.14 Whites (White Army)

Counter-revolutionary armed forces that fought against the Bolsheviks during the Russian Civil War. The White forces were very heterogeneous: They included monarchists and liberals - supporters of the Constituent Assembly and the tsar. Nationalist and anti-Semitic attitude was very common among rank-and-file members of the white movement, and expressed in both their propaganda material and in the organization of pogroms against Jews. White Army slogans were patriotic. The Whites were united by hatred towards the Bolsheviks and the desire to restore a ‘one and inseparable’ Russia. The main forces of the White Army were defeated by the Red Army at the end of 1920.15 Reds

Red (Soviet) Army supporting the Soviet authorities.16 German colonists/colony

Ancestors of German peasants, who were invited by Empress Catherine II in the 18th century to settle in Russia.17 Pushkin, Alexandr (1799-1837)

Russian poet and prose writer, among the foremost figures in Russian literature. Pushkin established the modern poetic language of Russia, using Russian history for the basis of many of his works. His masterpiece is Eugene Onegin, a novel in verse about mutually rejected love. The work also contains witty and perceptive descriptions of Russian society of the period. Pushkin died in a duel.18 Lermontov, Mikhail, (1814-1841)

Russian poet and novelist. His poetic reputation, second in Russia only to Pushkin's, rests upon the lyric and narrative works of his last five years. Lermontov, who had sought a position in fashionable society, became enormously critical of it. His novel, A Hero of Our Time (1840), is partly autobiographical. It consists of five tales about Pechorin, a disenchanted and bored nobleman. The novel is considered a classic of Russian psychological realism.19 Marshak, Samuil Yakovlevich (1887-1964)

Writer of Soviet children's literature. In the 1930s, when socialist realism was made the literary norm, Marshak, with his poems about heroic deeds, Soviet patriotism and the transformation of the country, played an active part in guiding children's literature along new lines.20 Spanish Civil War (1936-39)

A civil war in Spain, which lasted from July 1936 to April 1939, between rebels known as Nacionales and the Spanish Republican government and its supporters. The leftist government of the Spanish Republic was besieged by nationalist forces headed by General Franco, who was backed by Nazi Germany and fascist Italy. Though it hadSpanish nationalist ideals as the central cause, the war was closely watched around the world mainly as the first major military contest between left-wing forces and the increasingly powerful and heavily armed fascists. The number of people killed in the war has been long disputed ranging between 500,000 and a million.